Why Space Data Will Be More Valuable than AI

- The commoditization of AI is elevating the strategic value of proprietary space data

- The space industry’s current model of vertical integration presents economic challenges related to cost and scale

- The “TSMC Moment” for the industry would separate hardware infrastructure from the application layer

- Increased specialization in either data infrastructure or intelligence applications may lead to more sustainable business models

The AI models that currently command premium pricing are on a clear trajectory toward commoditization. As open-source alternatives narrow the performance gap and accuracy thresholds approach practical ceilings, the value equation in technology is shifting: intelligence is becoming abundant, while unique data is emerging as the scarcest resource in the digital economy.

Space companies, sitting atop humanity’s most comprehensive planetary monitoring infrastructure, should be positioned to capture enormous value in this transition. Instead, many are diluting their advantage by trying to compete on both sides of an equation where specialization increasingly determines success.

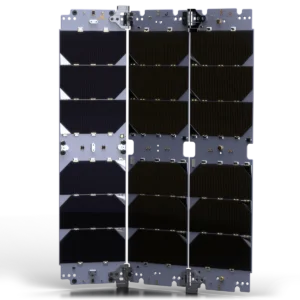

This dynamic crystallized during a recent conversation between Raycho Raychev, founder of satellite manufacturer EnduroSat, and James Mason, Chief Space Officer at Planet, who oversees one of Earth’s largest observation satellite fleets. Their exchange revealed a strategic trap that threatens to undermine the industry’s economics just as the opportunity is expanding

Mason pointed to a specific inflection point that should alarm any space company investing heavily in proprietary AI:

“We saw only with this algorithm, DeepSeek… The moment you put for free some model that is even not as advanced or whatever, but you just put it there, it immediately creates a reality check.”

As Raychev noted, once models reach very high accuracy levels, “you don’t care which model actually use. So the models become a commodity.” Mason’s own assessment confirms where value is heading: “I think the models will become commoditized and then the value will be in the unique data or the like actual service provision.”

This isn’t distant speculation—it’s a transition already underway. And it fundamentally changes what space companies should be building.

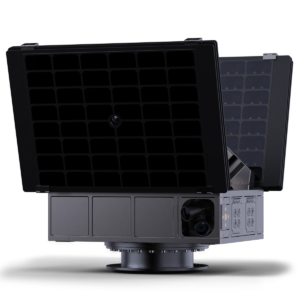

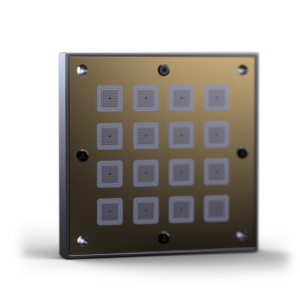

Space-based sensing offers several structural advantages that create defensible positions. Mason identified critical gaps in what’s available: high-resolution 3D global mapping at centimeter scale, and “high frequency persistence… always on nighttime through clouds, SAR data at high frequency… to be able to detect any change that’s happening anywhere in the world.”

This persistent monitoring capability could enable what Mason calls “autonomous tasking”—using AI to orchestrate sensors based on model uncertainty rather than human intuition. A model tracking container counts at ports could signal when it needs fresh SAR data to collapse uncertainty. The model itself drives data collection based on information value.

These capabilities remain theoretical because of a problem Raychev identified with brutal clarity:

“If you take all the money ever invested in your space initiative and you divide them realistically by the total amount of gigabytes… it starts to become insanely expensive.”

The math is stark: thousands of dollars per gigabyte for some radar systems. At those unit economics, building AI capabilities on top becomes impossible. Yet companies continue trying.

The conversation repeatedly returned to a central question: why are so many space companies trying to do everything themselves?

Raychev pushed on the underlying pathology:

“The founders of those companies are exceptionally smart people, but they’re so in love with certain type of technology that they get confined very fast into the technology. And they say, wow, it’s an amazing technology. I wonder what I can do with it.”

This technology-first orientation leads to unsustainable vertical integration. Companies are simultaneously building satellites, operating ground stations, processing data, developing analytics platforms, and now creating proprietary AI capabilities. Each of these demands world-class talent and significant capital.

Mason observed the fragmentation problem:

“You have sort of like, fragmentation that you have like 20 companies all trying to do the same thing… So all that talent and money gets spread over all these companies, and none of them can get to that scale.”

It’s a vicious cycle: costs stay high because no one achieves scale, but you can’t drop prices to expand markets when costs are high. Meanwhile, you’re also competing on AI development with labs that have already invested billions in model capabilities that are trending toward commoditization.

Raychev articulated a restructuring vision:

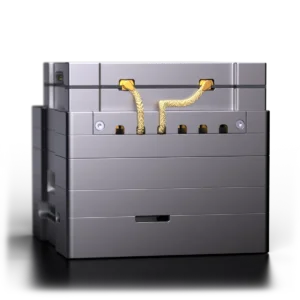

“I really think the space sector would win absolutely big time if you have the TSMC moment of the space industry… at the cost that objectively makes the downlink of data so low in fact that you can do the final application models… without ever touching a satellite.”

The TSMC analogy is precise. Taiwan Semiconductor doesn’t design chips—it manufactures them at scale and quality that makes it indispensable. Fabless chip designers focus on innovation while outsourcing production. This specialization drove an explosion in semiconductor design precisely because startups didn’t need billion-dollar fabrication facilities.

Raychev’s vision extends this:

“My vision, my dream is in the next two three years to see fleet operators like constellation players of the future, not having even one space engineering departments, not having a mission control.”

The implication is clear: the industry needs to bifurcate. Infrastructure providers should focus exclusively on deploying sensors and delivering data at breakthrough price points—accepting thin margins while capturing scale. Intelligence providers should consume data from these platforms and build vertical applications, focusing on domain expertise without carrying spacecraft development costs.

Excelling at both requires fundamentally different organizational capabilities. Aerospace engineering and data science demand distinct talent pools. Infrastructure requires long-cycle, capital-intensive thinking. Intelligence platforms benefit from rapid iteration. These rhythms are difficult to balance within one organization, especially when capital is increasingly scarce.

For existing space companies, the strategic question centers on focus. Mason was candid about the pressure: “It’s tough being a public company. And a lot of the focus is just on getting to profitability and truly becoming a business.”

The companies most at risk may be those maintaining significant investments on both infrastructure and intelligence without dominant position in either. When asked hypothetically about investing $100 million in space today, Mason’s answer was revealing: he’d choose communications, or Earth observation only if using an infrastructure provider to avoid building everything in-house.

For new entrants, the opportunity is to build intelligence companies that treat data infrastructure as an available resource. Focus on analytics and applications where iteration speed and specialization create advantages, not on constructing satellites.

The underlying opportunity for the space industry is substantial—Earth observation data becomes increasingly valuable as AI capabilities expand. But as Mason observed about industry consolidation: “I think there’s quite a few companies that I think will not survive the next few years.”

Over the next several years, we’ll likely see clearer segmentation between “data infrastructure” and “orbital intelligence” companies, with distinct valuations and competitive dynamics. Infrastructure players that achieve significant scale could emerge as essential platforms. Intelligence players that build deep domain expertise could achieve stronger margins by focusing on applications rather than spacecraft.

The strategic question is whether companies will capture value by specializing in what they do best, or dilute it by competing across the entire value chain. The advice both participants offered to next-generation entrepreneurs applies equally to existing players: don’t fall in love with the technology, fall in love with the problem you’re solving.

In a market where algorithmic capabilities are converging while unique data sources remain scarce, the winners will be those who recognize that focus creates defensible positions. The losers will be those still trying to be everything to everyone when the market demands specialization.

This article is based on an episode of The Frame Podcast, hosted by EnduroSat.

Tune in for the complete discussion on your favorite platform.