From 10K to 100K Satellites in Orbit: What Will It Take?

- The Coming Consolidation: Within 3-5 years, a handful of infrastructure specialists will serve thousands of data-focused customers as the industry scales from 10,000 to potentially 100,000 satellites. Companies that recognize what business they’re really in will thrive; those clinging to full-stack vertical integration will struggle to survive.

- The Identity Confusion: Data companies are building their own satellites, ground stations, and manufacturing facilities—the equivalent of Uber deciding to manufacture cars and build roads. This misalignment between business identity and resource allocation is preventing profitability across the industry.

- The Unit Economics Trap: Vertical integration forces companies to amortize massive infrastructure costs across limited data sales, creating cost-per-gigabyte economics that make sustainable business models nearly impossible. Most companies avoid calculating their true fully-loaded costs because the numbers are shocking.

- Manufacturing Without Markets: Companies are rushing to build “mass manufacturing” capacity for millions of satellites when their actual business needs are hundreds or thousands. This premature scaling locks capital into fixed assets without corresponding demand, compounding the profitability challenge.

- The Great Unbundling Solution: The industry is separating into horizontal layers—specialized infrastructure providers, payload innovators, and data/application companies. This mirrors successful tech industries where countless applications run on relatively few platforms, multiplying the effective talent pool by 3-4x.

After decades of bespoke, vertically-integrated approaches to satellite development that have consistently failed to deliver sustainable economics, the space industry is finally experiencing its platform revolution moment.

Here is the paradox: most organizations identifying as “space companies” are actually data businesses that have made the decision to simultaneously be space infrastructure manufacturers. This isn’t a minor inefficiency—it’s a structural path to bankruptcy that’s destroying otherwise viable ventures.

The numbers tell a stark story. Despite functional technology, successful launches, and satellites delivering data as designed, the vast majority of constellation operators remain nowhere near profitability. The problem isn’t technical execution. It’s a fundamental confusion about what business these companies are actually in, compounded by an inherited obsession with vertical integration that made sense in the shuttle era but is financial suicide today.

In a recent conversation, EnduroSat founder and CEO Raycho Raychev sat down with Paul ‘Rusty’ Thomas, CEO of EnduroSat USA and former executive at SpaceX and Amazon Leo (formerly Project Kuiper), to discuss the structural challenges facing satellite companies. Their exchange illuminates how intelligent founders repeatedly make the same irrational decision—and why the industry’s structure needs fundamental transformation

The pattern repeats across the industry with remarkable consistency. A team identifies a valuable data problem—precision agriculture, maritime tracking, environmental monitoring, disaster response. They develop innovative sensor technology or analytics approaches. They secure initial funding. And then, inexplicably, they decide to spend 60-70% of their resources and capital building satellites from scratch.

Raychev identifies what he believes is a critical blind spot in the industry: “I always tend to believe and see in the space industry what I think is heavily not understood even by a lot of colleagues, that about 75 to 80% of the space companies are actually data companies. They generate some kind of valuable data, and then they sell it to terrestrial businesses on the ground via services or applications.”

Yet these data companies consistently make the same error: believing that building their own infrastructure is the cheaper, better way forward. Raychev offers a pointed analogy to illustrate the strategic absurdity: “It’s like you’re being an Uber and deciding tomorrow morning for 60, 70% of your time and money and capital basically to build cars and to build roads.”

The comparison makes the problem obvious. No one would argue Uber should manufacture vehicles or construct highway infrastructure. Yet in space, this thinking remains dominant. Raychev suggests the root cause is a confusion of priorities—founders are “in love with the technology they like instead of being in love with the challenge they solve.”

This creates what might be called the engineer’s fallacy: confusing technical capability with business strategy. Being skilled at engineering doesn’t mean you should engineer everything. Being capable of building satellites doesn’t mean you should build your own satellites. The question isn’t whether you can—it’s whether you should, and whether doing so advances or undermines your actual business objectives.

The consequences of this confusion manifest most clearly in unit economics. Rusty identifies the fundamental structural problem: “When you try to do it yourself, it means you’re never going to be profitable” because you must “amortize all that cost across all those layers.”

Consider what vertical integration actually requires:

- Satellite bus development and iteration

- Manufacturing facilities and equipment

- Quality assurance systems and testing infrastructure

- Launch integration capabilities

- Ground station networks

- Mission operations centers

- Ongoing R&D across multiple disciplines

All of this must be funded and maintained before optimizing the actual data product that customers pay for. The capital requirements are staggering. The timeline stretches to years. And critically, these infrastructure costs must be recovered through data sales—creating a cost-per-gigabyte that makes profitability nearly impossible.

Raychev describes the accounting reality that few companies want to face directly: “If you take the total expenditure done for you getting your infrastructure in orbit and operating it nominally for the lifetime of the satellites, and you divide it by the amount of data… this gives you the real cost per gigabyte of acquisition of data, and then you’ll be shocked about the actual cost per gigabyte of these companies.”

The uncomfortable truth is that many companies structure their business models around aspirational future pricing rather than current reality. They focus on marginal costs of data delivery rather than fully loaded infrastructure costs. They project that somehow, at sufficient scale, the unit economics will transform. But scale itself requires capital, and the infrastructure burden grows alongside the constellation. The mathematics of vertical integration create a profitability treadmill that most companies never escape.

Perhaps nothing illustrates the strategic confusion better than what Raychev calls “manufacturing theater”—the rush to build large-scale production facilities without corresponding market demand.

Raychev draws a critical distinction that the industry often misses: “Most of the world in our industry doesn’t understand what mass manufacturing means. There is serial production, which means like a few hundred, few thousand units. And that’s okay. There is mass manufacturing of using the technologies to build a million parts.”

The mismatch becomes dangerous when companies build for the latter while their business requires the former. As Raychev warns: “If you start building a factory for a million satellites, but there is actually a need for 100 or 1,000 or even 10,000, you’re already kind of dead financially.”

This premature scaling creates multiple problems. It locks capital into fixed assets. It creates organizational overhead. It demands volume to justify the investment, potentially driving poor strategic decisions about which customers to pursue or what missions to accept. Most perversely, it happens because founders believe this is what “serious” space companies do—another case of imitating form without understanding function.

Rusty provides valuable context from SpaceX’s approach to manufacturing scale. The company hired automotive manufacturing executives to bring production techniques from an industry that builds thousands of complex units—methods for assembly line optimization, quality control at scale, and supply chain management for high-volume production. But critically, as Rusty notes, this happened after SpaceX had achieved scale and proven the business model, not before. The sequence matters enormously: first prove the demand exists, then build the capacity to meet it.

o what’s the alternative? Both Raychev and Rusty point toward what might be called the Great Unbundling of the satellite industry—a separation into distinct horizontal layers where companies can develop genuine competitive advantages.

Rusty explains the logic through a powerful analogy: “Imagine if every app developer for the iPhone developed their own iPhone, and then they tried to sell this to everybody. It makes no sense. You should have all these great applications that can go on the common iPhone… and there’s more than one type of iPhone, there’s an iPhone and there’s the Google phone and there’s the other phones. You don’t have just one phone, but you don’t have a single phone that you develop for every application.”

The parallel to satellites is clear: companies should focus on their differentiated application or data service, not on building bespoke infrastructure for each mission.

The Emerging Industry Structure:

Launch Layer: A set of reliable launch providers offering various payload capacities and orbit options at competitive prices. Companies can select the appropriate launch service for their mission requirements.

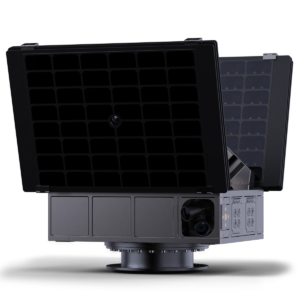

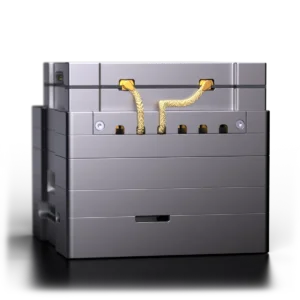

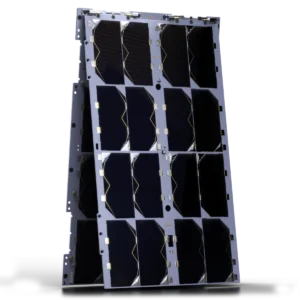

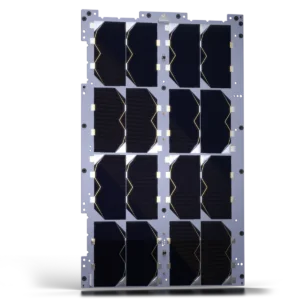

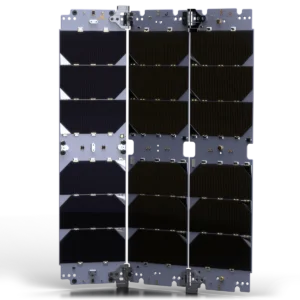

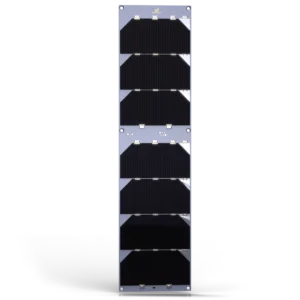

Infrastructure Layer: A small number of satellite bus manufacturers focused on cost, reliability, flexibility, and delivery speed. These companies master the common spacecraft subsystems—power, avionics, attitude control, propulsion, structure, and thermal management—that remain fundamentally similar across different missions.

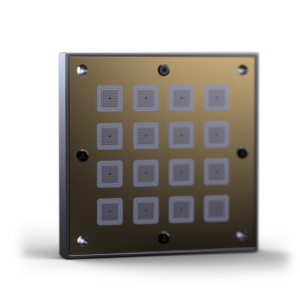

Payload Layer: Specialized sensor and instrument developers creating differentiated technology. This is where true innovation in data collection happens—novel optical systems, advanced radar capabilities, new sensing modalities.

Application Layer: Data companies focused entirely on analytics, services, and customer value. This is where most current “satellite companies” actually belong—turning raw data into actionable insights for specific industries.

Rusty makes the case for specialization explicit: “The efficient way is once you have the infrastructure of launch, everybody shouldn’t develop their own launch vehicle. That doesn’t make any sense at all. Everybody shouldn’t develop their own bus. They should be able to spend their money and their capital investment and their R&D investment at that mission layer, maybe at the payload element.”

This separation multiplies the effective use of scarce talent. Rusty identifies talent dilution as a serious risk as the industry scales: “If you have launch is hard and the bus and satellite level is hard, and then the mission level is hard, and you try to focus these new companies at all these areas, that requires a lot of talent.”

By concentrating talent at appropriate layers, he argues, “you can get essentially 3 or 4 times as much effects out of the talent pool that you have as you expand the talent pool.”

This efficiency gain matters increasingly as the industry scales. Rusty projects explosive growth ahead: “I really think there’s going to be not 7 or 8,000 satellites. I think there’s going to be 20, 50, 100,000 satellites in space in the not too distant future.” Supporting this expansion requires maximizing how effectively limited aerospace talent can be deployed—something vertical integration actively prevents.

Read more about the vertical integration trap and the horizontal shift in our article “How to Unlock the Space Economy?”

This transformation creates clear winners and losers. Companies that recognize they’re fundamentally data businesses—and embrace infrastructure partnerships rather than in-house development—gain years of development time and preserve capital for actual differentiation. Those clinging to vertical integration without SpaceX-scale resources face mounting losses as infrastructure costs compound.

The coming consolidation will reshape the competitive landscape. While tens of thousands of satellites may orbit Earth within a decade, most will come from a handful of infrastructure specialists serving thousands of data-focused customers. This mirrors the structure of successful technology industries: countless applications running on relatively few platforms.

The implications extend beyond individual company strategy. Investors need to distinguish between infrastructure plays requiring massive capital and long timelines versus application plays that can achieve profitability faster with less capital. Customers will benefit from the cost reductions that horizontal specialization enables. And talent can focus their expertise where it creates maximum value rather than being spread across impossible-to-master domains.

The most uncomfortable implication? Many current “satellite companies” may need to admit they’re in the wrong business—or more precisely, that they’ve confused which business they’re actually in. Pivoting away from years of infrastructure investment is painful, but it’s less painful than bankruptcy.

The satellite industry has reached a critical juncture. The technology to put sophisticated sensors in orbit has matured. Launch costs have plummeted. The market for space-derived data is expanding rapidly. Everything is in place for a flourishing industry—except the business models.

The Great Unbundling isn’t a distant future scenario. It’s already underway, driven by the simple economics that make vertical integration untenable for most players. The companies that recognize they’re data businesses first—and embrace specialized infrastructure rather than building it themselves—will capture the market. Those that continue the pretense of being full-stack space companies will join the long list of technically impressive but financially failed ventures.

Raychev frames the fundamental question the industry must answer: “How do you produce or manufacture them in the most efficient way possible? It’s not to brag, ‘Well, my satellite is bigger than yours,’ or ‘My number of satellites is bigger than your number of satellites.’ We inevitably lose sight of why you exist in the first place.”

The satellite industry isn’t failing because space is hard. It’s failing because companies keep making it harder than it needs to be—building infrastructure they don’t need, optimizing for metrics that don’t matter, and forgetting that their actual business is delivering valuable data, not constructing impressive spacecraft.

The winners will be those who remember what business they’re really in.

This article is based on an episode of The Frame Podcast, hosted by EnduroSat.

Tune in for the complete discussion on your favorite platform.